While the MiG-15 Fagot impressed Western observers during the Korean War, there were still considerable problems with its handling as it approached the speed of sound. It became so uncontrollable and near-sonic speeds, which it could reach in a dive, the speed brakes automatically deployed in order to prevent the pilot from exceeding speeds where he could control the aircraft. These problems were not limited only to the MiG-15 or to the Russians. The first swept-wing jet fighters all experienced similar problems as designers and engineers learned about near-sonic and supersonic speeds and how to make aircraft controllable at those Mach numbers. The U. S. F-86 Sabre, which fought the MiG-15 over Korea, had similar problems, and modifications were made to the wings and the tail surfaces to solve them.

In Russia, the MiG design bureau began making changes to the MiG-15 to solve these problems as well. They designated the new design SI, while the Soviet Air Force called it the I-330. Two prototypes, one converted from a MiG-15 airframe and designated SI-1, and the other converted from a MiG-15bis airframe and designated SI-2, were constructed. They had a completely redesigned wing, a longer fuselage, and a larger vertical tail when compared to the MiG-15. The SI-1 was used only as a static airframe and for wind tunnel testing, while the SI-2 began the flight test program. Strangely enough, the new design did not incorporate an all-flying tail but retained the conventional fixed horizontal stabilizer and moveable elevator combination instead. The benefit, indeed the necessity, of the all-flying tail for near-sonic and trans-sonic flight was already clearly recognized in the West. Later variants of the F-86 Sabre were fitted with this feature, and it would become standard on all subsequent American supersonic fighter aircraft.

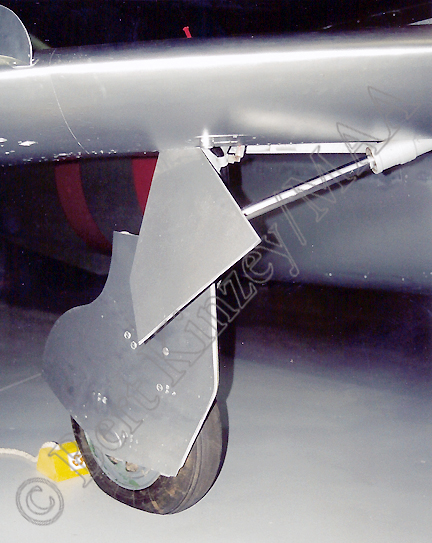

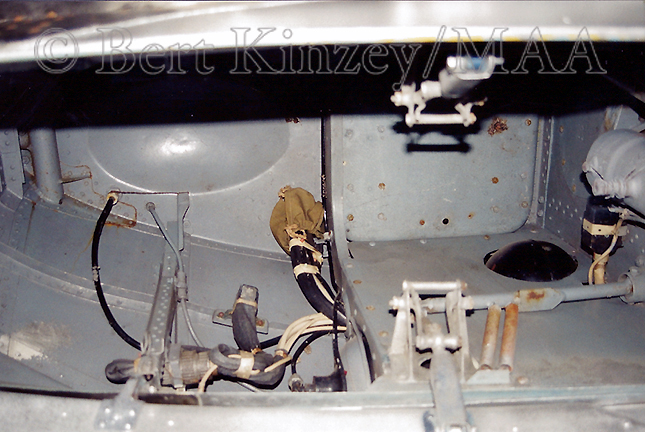

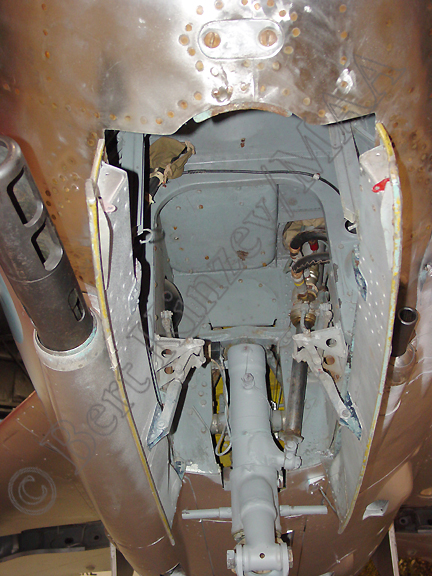

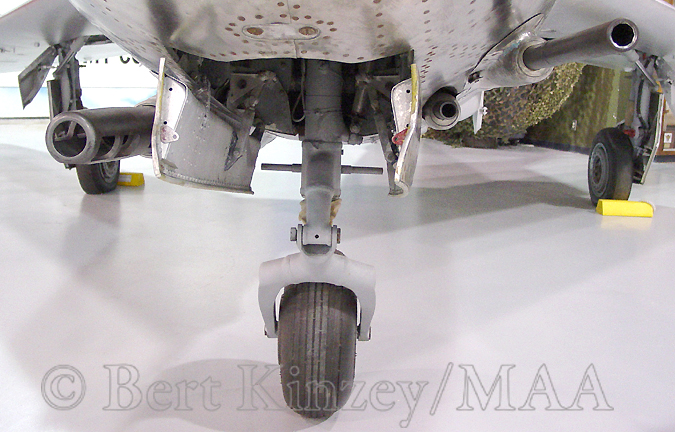

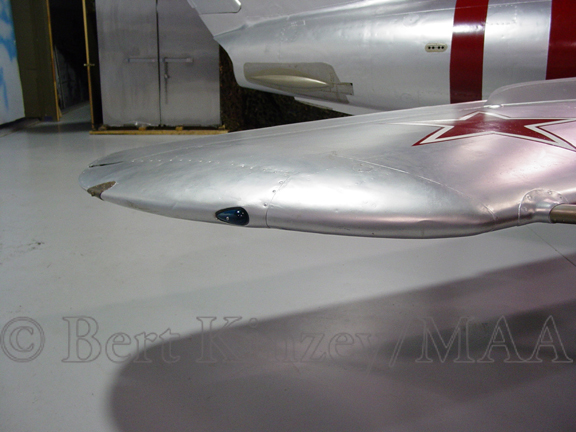

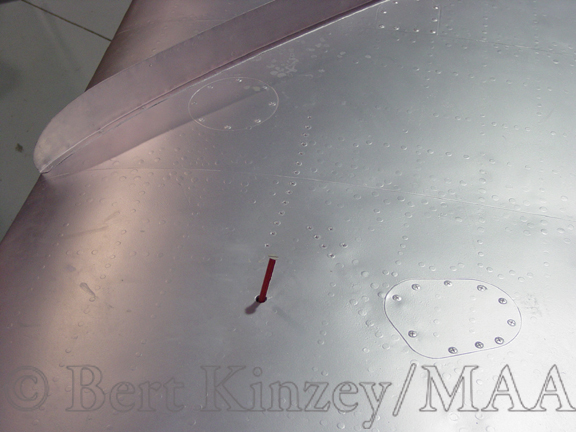

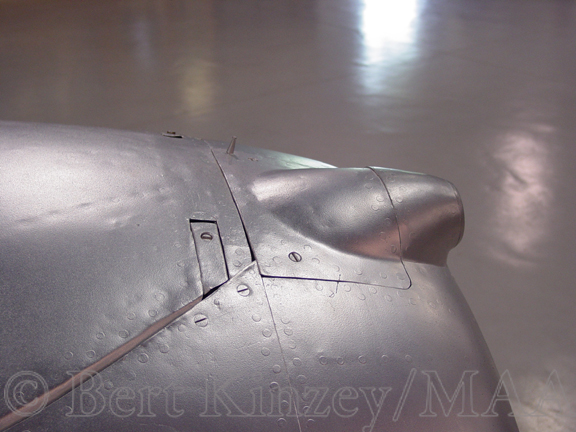

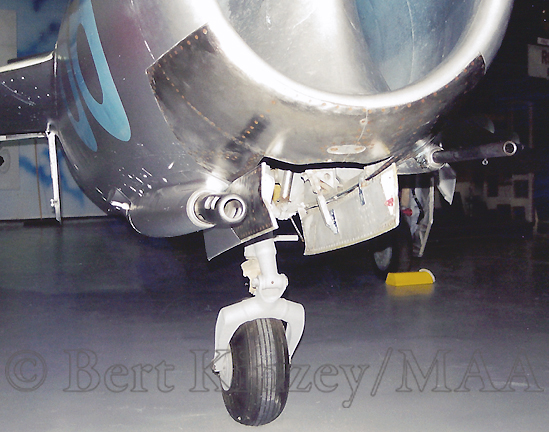

Of the changes made, the new wing was the most obvious. It was thinner than the one used on the MiG-15, and it had rounded tips. The leading edge was not straight. The inboard part of the leading edge had a 49-degree sweep, while the outer section had a sweep of only 45.5 degrees. There were three fences on the upper surface of the wing rather than just two as found on the MiG-15. These fences prevented the airflow from sliding down the swept wing. The fuselage was lengthened slightly less than four feet, and a strake was added under the aft fuselage to improve lateral stability. Other design changes were made to the landing gear and elsewhere on the aircraft, but these were generally minor in nature. Many design features of the MiG-15 were retained, and many parts remained interchangeable between the designs. The armament of two NS-23 23-mm cannons and one NS-37 37-mm cannon remained unchanged and was fitted to the prototype.

Flight testing began on February 1, 1950, but after only a few weeks, the SI-2 was destroyed in a crash that also killed the test pilot. Two more prototypes soon replaced the lost aircraft, and the test program began again. During the testing, these aircraft demonstrated successful flight at Mach 1.03. In level flight, the prototypes were only about thirty miles-per-hour faster than the MiG-15bis, but the real advantage was the improved handling at high speeds. The test program concluded on June 20, 1951, and two months later, the aircraft was ordered into production as the MiG-17. NATO would later assign the reporting name, Fresco, to the new fighter.

In addition to the single 37-mm cannon and two 23-mm cannons, the MiG-17 had a single hard point under each wing for carrying external stores. When not fitted with external fuel tanks, bombs, rockets, or rocket pods could be carried on pylons installed on these hardpoints.

Although the MiG-17 production line began deliveries in August 1951, it wasn’t until June 1953 that the MiG-17 was put on public display, and Western observers initially thought it was a new variant of the MiG-15. To a large extent, it actually was, but the Soviet designation as a new aircraft was soon revealed. With the Fresco entering operational service in late 1951, it may seem that there was plenty of time for the new fighter to join the MiG-15 in Korea, but the Russians decided to keep it in their own fighter squadrons rather than evaluating it in combat alongside its predecessor. Meanwhile, some MiG-17s were modified and used as test aircraft for proposed variants and to evaluate new equipment.

One of the more interesting modifications was called Project SN. A solid nose with three 23-mm cannons was installed, and the cannons could be moved up or down in slots rather than being fixed. With this armament, the air inlet for the jet engine had to be replaced with two smaller inlets located in the wing roots.

Realizing the need for an all-weather interceptor, two developments of the MiG-17 were tested soon after the Fresco entered service. These were designated SP-2 and SP-7. The later was fitted with an Izumrud radar system mounted in the nose. The search radar was under a dome at the top of the intake lip, and the tracking radar was mounted inside a dome at the center of the divider in the intake. The aircraft was armed with three 23-mm cannons, because replacing the 37-mm cannon on the right side with a smaller and lighter 23-mm weapon helped compensate for the extra weight of adding the radar in the nose. The SP-7 went into limited production as the MiG-17P, and production aircraft were assigned to Soviet air defense squadrons of PVO Strany, the Russian equivalent of the U. S. Air Force’s Air Defense Command. NATO gave the MiG-17P the reporting name of Fresco B. Standard MiG-17s were then given the designation Fresco A.

By the early 1950s, the means of boosting the thrust of a jet engine with an afterburner had become known, and these devices began to appear on test aircraft and then on the production lines. The afterburner was very simple, consisting of an extended exhaust pipe into which jet fuel could be dumped to increase the volume and speed of the exhaust gases. But this increase in thrust was for temporary use only, because it came at the price of a considerably higher consumption rate of fuel.

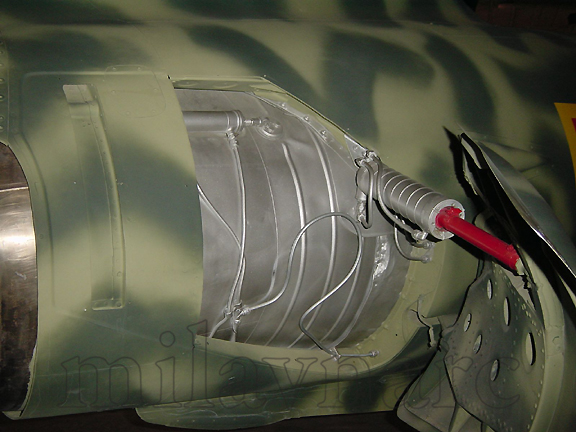

The Russians modified the VK-1A engine by adding a short afterburner and redesignating the powerplant the VK-1F. The F stood for forsirovannyy, which is Russian for boosted. The maximum thrust was boosted from 5,950 pounds for the VK-1A to 7,451 for the VK-1F. The engine was installed in a SF prototype converted from a MiG-15bis airframe. With the new powerplant installed, the aft end of the afterburner nozzle extended beyond the tail section of the fuselage by several inches. Flight testing quickly demonstrated a marked increase in performance, particularly in time-to-climb numbers.

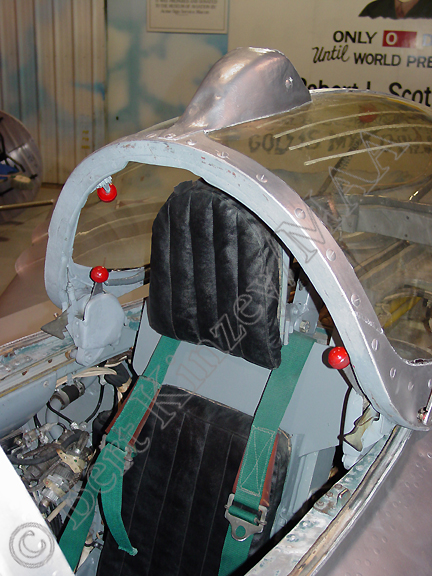

Other changes were made to the design, with the most noticeable being larger speed brakes on the aft fuselage which had much larger fairings covering their actuators. Small air intake slots were located near the top of the aft fuselage to improve cooling within the engine compartment, and the flare dispenser was moved from the right side of the fuselage to the right side of the vertical tail. Of special interest to the pilot, a new ejection seat was installed that was far more advanced and safer in operation than the one used in the MiG-15 and the MiG-17 Fresco A. The internal armament remained one 37-mm and two 23-mm cannons.

The new variant was placed in production as the MiG-17F, which NATO designated the Fresco C. It became the most numerous of all MiG-17 variants, with more than 8,000 being produced. The MiG-17F also had the distinction of being the first operational aircraft in the Soviet Air Force to be equipped with an afterburner. It would become one of the most widely exported combat aircraft of all time, and it proved to be very effective in combat, even when fighting against aircraft which, at least on paper, seemed to be vastly superior.

With the day fighter version of the aircraft now fitted with an afterburner, the next logical step was to develop all-weather interceptor versions that likewise had the benefit of the extra thrust of an afterburner. The performance figures of the MiG-17P Fresco B had suffered due to the extra weight of the radar system and its associated equipment. The addition of an afterburner would go a long way in solving this problem. Accordingly, the existing MiG-17P was modified to accept the new afterburning VK-1F engine.

The test aircraft was designated the SP-7F, and after testing, the new variant was placed into production as the MiG-17PF. NATO assigned the reporting name Fresco D to the new interceptor. Early production MiG-17PFs had the same RP-1 radar system used on the earlier MiG-17P Fresco B, but this was later upgraded to the RP-5. Armament was three NR-23 cannons with eighty rounds per gun. The substituting of a third 23-mm cannon for the 37-mm cannon used on the day fighters was again a way to compensate for the extra weight in the nose caused by the installation of the radar equipment. Nevertheless, the MiG-17PF had an empty weight of more than 550 pound heavier than the MiG-17F. It should also be noted that the installation of the radar necessitated moving the S-13 gun camera and its associated fairing to the right side of the intake lip instead of being near the top as it was on the day fighter variants.

The development of air-to-air missiles in the West did not go unnoticed by the Soviets, and they began working on their own designs. The first to reach operational status was the RS-2U, known as the AA-1 Alkali by NATO. This was a semi-active homing radar guided missile that rode the beam generated by the radar in the aircraft. This is the same principle used by the U. S. AIM-7 Sparrow missile. The first aircraft to be equipped to carry the RS-2U was the MiG-17PM. The three 23-mm cannons of the MiG-17PF were deleted, making this new version of the aircraft the first Soviet fighter to be armed solely with missiles. Two APU-4 launch rails were mounted under the inboard section of each wing, providing a total of four missiles for the aircraft. The RP-2U radar system was installed to search for targets, lock on, and then guide the missiles to their targets.

The MiG-17PM was assigned the reporting name, Fresco E, by NATO. It was not built in great numbers, leaving the MiG-17PF as the primary all-weather interceptor in PVO until it was replaced by radar-equipped MiG-19PMs and MiG-21C Fishbeds.

Not only was the MiG-17 widely exported by the Soviet Union, it was also built in two other countries as well. Communist China produced MiG-17Cs as the Shenyang J-5. Although the Russians never built a two-seat training version of the MiG-17, the Chinese did, calling it the JJ-5. It was essentially a J-5 with the two-seat cockpit arrangement of the MiG-15UTI Midget installed in place of the standard single cockpit. The JJ-5 also had a small radar installed in the upper lip of the engine air inlet. Like most MiG-15UTI trainers, it was armed with a single 23-mm cannon.

Poland produced a version of the MiG-17F as the Lim-5. They also built a limited number of Lim-5P reconnaissance variants. An attempt to develop a modified ground attack variant as the Lim-5M, and subsequently the Lim-6, met with little success, and few were produced. The Lim-6bis was an improvement over the Lim-6, but only seventy were built. The Lim-6R and Lim-6MR were photo-reconnaissance variants. When the Chinese and Polish production numbers are added to those of the Soviet Union, a total of more than 10,000 MiG-17s were produced.

Over many years of operational service, MiG-17s were flown by the air forces of Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Communist China, Republic of the Congo, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Egypt, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Indonesia, Iraq, Hungary, Libya, Madagascar, Mali, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, North Korea, North Vietnam, Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Somalia, Somaliland, Sri Lanka, Syria, Tanzania, Uganda, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

AT THE NATIONAL MUSEUM

OF THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE

Perhaps the most famous MiG-15 in the world today is the one on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. The aircraft was flown to South Korea by defecting pilot, Lieutenant No Kim-Sok, on September 21, 1953, where he received a $100,000 reward for delivering the aircraft to the United States. It was first tested and evaluated in Okinawa, and then it was moved to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base for additional testing. It was offered back to its “rightful owners” by the United States, but the Soviets, who had denied their participation in the Korean War, did not accept the offer. It was then given to the National Museum of the United States Air Force, where it remains on display to this day.

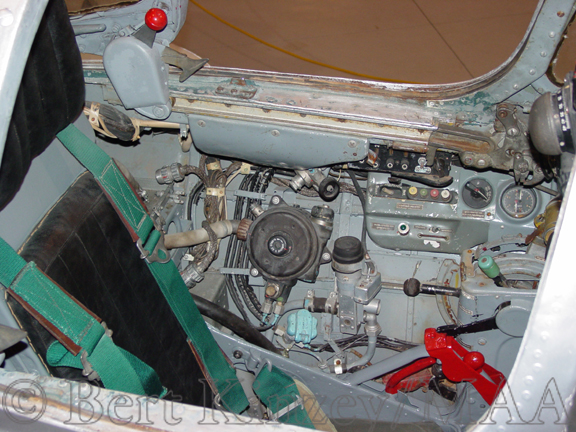

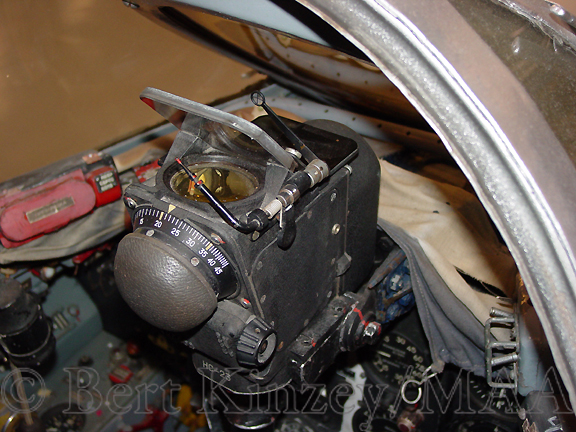

In August 1979, Bert Kinzey & Bill Slatton were given permission to photograph and measure the aircraft extensively and to analyze its details. While the aircraft is basically a MiG-15bis, there are clearly some features that indicate that some parts from a MiG-15 were substituted at some point in time, perhaps to repair damage. Both early and late MiG-15bis features can be found on the aircraft.

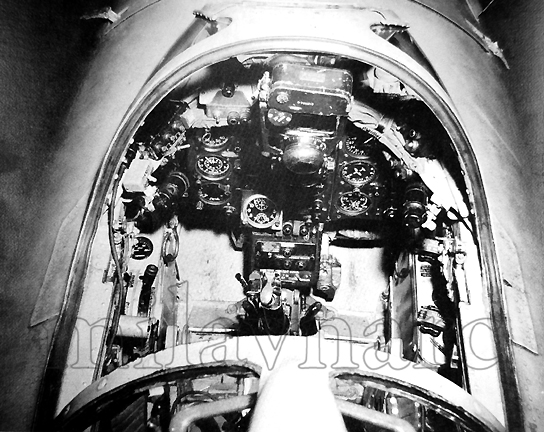

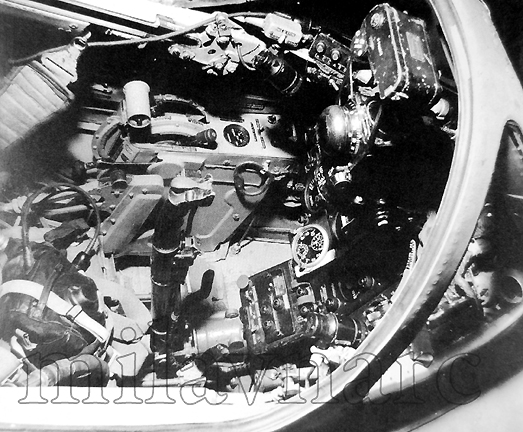

Most of the photographs in this set were taken by Bert Kinzey during that visit in August 1979. Most are in color, and were originally color slides. A few black and white supplemental photographs are also provided. Three additional black and white cockpit photos, taken by the U. S. Air Force, are also included in this photo set to show what the cockpit looked like when the aircraft was surrendered to the United States.

Detail & Scale thanks the director and staff of National Museum of the United States Air Force for their cooperation in obtaining these detail photographs.

MiG-17 Fresco A Data

Length 36 feet, 11.5 inches

Wingspan 31 feet, 7 inches

Height 12 feet, 5.6 inches

Wing Area 243.7 square feet

Empty Weight 8,373 pounds

Gross Weight 11,464 pounds

Maximum Weight 13,078 pounds

Max Speed 680 miles per hour at sea level

Ceiling 51,180 feet

Range (internal fuel) 805 miles

Range (with external tanks) 1,280 miles

MiG-17F Fresco C Data

Length 36 feet, 11.5 inches

Wingspan 31 feet, 7 inches

Height 12 feet, 5.6 inches

Wing Area 243.7 square feet

Empty Weight 8,640 pounds

Gross Weight 11,784 pounds

Maximum Weight 13,393 pounds

Max Speed 717 miles per hour at sea level

Ceiling 54,462 feet

Range (internal fuel) 854 miles

Range (with external tanks) 1,230 miles

MiG-17PF Fresco D Data

Length 36 feet, 11.5 inches

Wingspan 31 feet, 7 inches

Height 12 feet, 5.6 inches

Wing Area 243.7 square feet

Empty Weight 9,220 pounds

Gross Weight 12,235 pounds

Maximum Weight 13,845 pounds

Max Speed 697 miles per hour at sea level

Ceiling 52,000 feet

Range (internal fuel) 612 miles

Mig-17 Fresco, MiG-17 Fresco A:

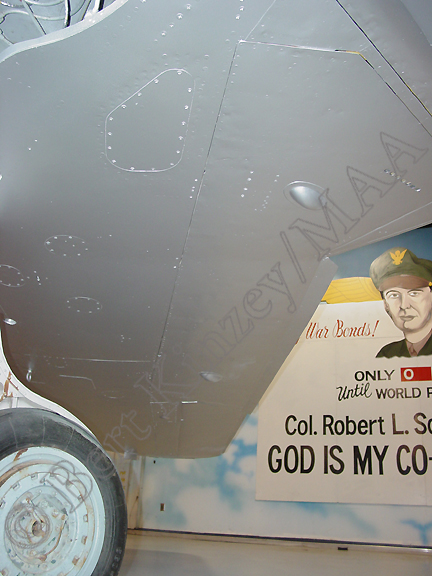

DEFECTION FROM CUBA

On October 5, 1969, Lieutenant Eduardo Jimenez of the Cuban Air Force defected to the United States in a MiG-17 Fresco A. He landed at Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, and parked his aircraft right next to Air Force One. President Nixon was at his home on Key Biscayne at the time, and the fact that a Cuban Air Force Fighter could fly through the air defenses of the Air Base and land next to the president’s aircraft caused considerable alarm and consternation. Permanent new procedures and safe passage corridors were put into effect, and detachments from the 48th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Langley Air Force Base were rotated on assignment to Homestead to increase the defenses. Flying F-106 Delta Dart all-weather interceptors, they replaced the 319th Fighter Interceptor Squadron with their F-104A Starfighters, which had provided air defense for Homestead AFB at the time of the defection. Further, the Army’s 31st Air Defense Artillery Brigade, consisting of two Hawk and one Nike Hercules battalions, enhanced procedures to improve the defense of South Florida. Following this incident, whenever President Nixon was at Key Biscayne, the alert status was increased in what was known as Operation Family Man. Family Man would remain in effect until Nixon left office.

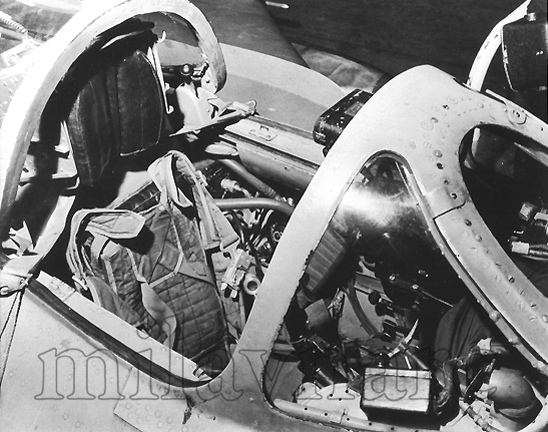

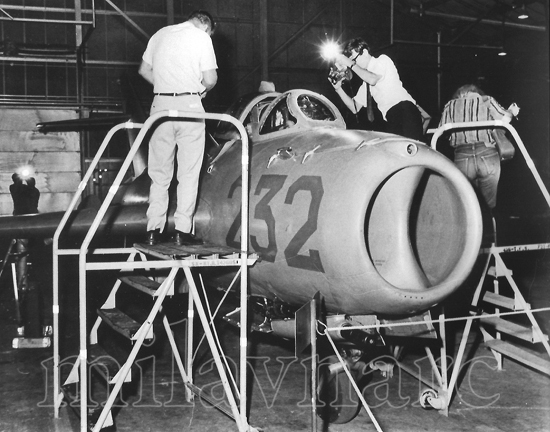

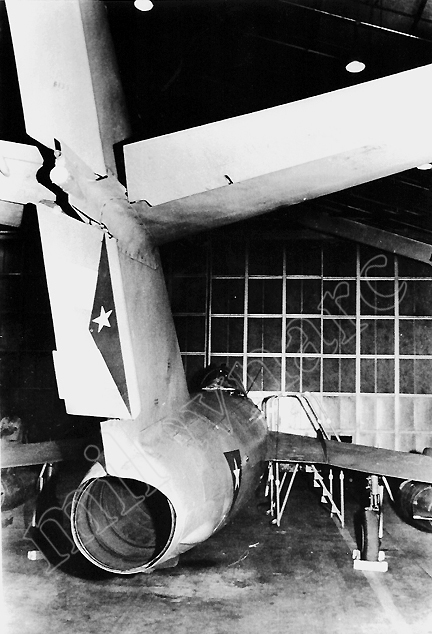

When the MiG-17 arrived at Homestead, it was immediately moved into a hangar and photographed and studied in great detail by military and civilian intelligence personnel. Detail & Scale was fortunate to obtain copies of photographs taken during the few days the aircraft was in Homestead. They were taken by Joe Nevers and provided through Bob Hanes. These photographs were originally published by Detail & Scale in The MiG-17 Fresco in Detail & Scale by Bill Slatton in 1979. Since that book is very rare, they are included again here in this photo set.

One of the interesting points about these photographs is that upon seeing them, some other writers stated that the Cuban insignia on the fuselage did not have the usual red surround around the blue triangle and white star. While it may appear that this is the case when looking at the photographs, it is not true. The red surround was present, but because it had almost the exact same reproductive value in black and white as the metallic color of the fuselage, it is almost invisible. Depending on the angle at which the rudder is viewed, the red stripes on it are also difficult to see in some photographs.

Detail & Scale thanks Joe Nevers and Bob Hanes for providing these rare photographs to us.

Mig-17 Fresco, MiG-17 Fresco A:

MUSEUM OF AVIATION, ROBINS AIR FORCE BASE GENERAL VIEWS AS RECEIVED

This photo set contains several pictures of a MiG-17 Fresco A shortly after it was received by the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base in Warner Robins, Georgia. This Fresco A was built in the Soviet Union in 1953 and exported to Bulgaria. It was used in both the interceptor and ground attack roles, and it was also used as a proficiency trainer for Bulgarian astronauts. These photographs were all taken by Bert Kinzey and show the aircraft as it was received by the Museum of Aviation while still in Bulgarian camouflage and markings.

This is the same aircraft as shown in MiG-17 Photo Set 3 after the aircraft had been repainted by the Museum of Aviation and placed on public display.

Mig-17 Fresco, MiG-17 Fresco A Details:

AT THE WAR EAGLES AIR MUSEUM

This photo set provides a very detailed look at the MiG-17 Fresco A on display in the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force base. The aircraft was received in operational condition by the Museum from the Bulgarian Air Force. After repainting it to represent a Soviet MiG-17 used in the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, the museum placed in on public display. This particular Fresco A was built in the Soviet Union in 1953 and was exported to Bulgaria. This is the same Fresco A as shown in MiG-17 Photo Set 2.

All photos in this set are copyright photographs from the Detail & Scale collection taken by Bert Kinzey. Appreciation is expressed to Bill Paul of the Museum of Aviation for making this detailed photography possible.

Mig-17 Fresco, MiG-17F Fresco C Details:

At National Museum of the United States Air Force

This photo set includes a few photographs taken of the MiG-17F Fresco C at the National Museum of the United States Air Force and a Lim 5 (Polish built MiG-17F) at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada. They are intended to show important physical differences between the MiG-17 Fresco A and the MiG-17 Fresco C.

Except for the lead photo included with this introduction and one of the detail photographs in the set, both of which were taken by Bert Kinzey, these photographs were taken by Jim Rotramel who retains the copyright. Military Aviation Archives thanks Jim for contributing these photographs.