F-4 Phantom

(U.S. Navy & Marine Versions)

Information File:

When it was introduced into service with the U. S. Navy, the McDonnell F4H-1 Phantom was clearly superior to any fighter then in the Air Force inventory. Only a few years before the Phantom made its first flight, the Air Force looked at Navy fighters as being inferior, so it was inconceivable that the Air Force would ever purchase a Navy aircraft that would eventually become its standard fighter for more than two decades. But the superiority of the Phantom over any Air Force fighter in service or on the drawing boards was so evident, that is exactly what happened. The Phantom was also the final proof that the best fighters in the world could operate from aircraft carriers, and as such, the introduction of the Phantom into fleet service was a defining and confirming event in the history of carrier aviation.

The Phantom began as an unsolicited study by McDonnell and was made as an attempt to keep that company involved in the production of jet fighters for the Navy. It was envisioned that the new fighter would eventually replace McDonnell’s F3H Demon as an all-weather fleet defense interceptor.

As originally conceived, the Phantom was an improved version of the Demon, and therefore called the F3H-G. It was a single-seat fighter-bomber with two engines and variable inlet ramps to control airflow to the powerplants. In 1954, the Navy assigned the AH-1 designation to the mockup, denoting the ground attack capability of the aircraft. But shortly thereafter, the four 20-mm cannon were replaced with Sparrow missiles, and the designation was changed to F4H-1. The Navy also requested that the new fighter be changed to a two-seat design.

The first flight by the initial XF4H-1 took place on May 27, 1958, and after a fly-off competition with Vought’s XF8U-3 Crusader III, McDonnell received its first orders for production aircraft. Because the name Phantom had been used on the previous McDonnell FH-1, the new fighter was officially named the Phantom II, but the II was usually dropped except for the most official use of the name.

Following the two XF4H-1 prototypes, forty-five F4H-1 production aircraft were delivered in small production blocks. Some changes in the aircraft’s design took place along the way, the most noticeable of these being a slightly higher rear canopy, redesigned air inlets, and a larger nose with a radome to house the APQ-72 radar. Shortly after these aircraft entered service, the Department of Defense ordered the standardization of aircraft designations throughout the U. S. military, and the F4H-1 was changed to F-4A.

These first production Phantoms were used for tests and evaluations as well as for a number of record setting flights, and a few saw service in the first fleet squadron to transition to the new fighter. But these were soon replaced by the F-4B, so the F-4As were reassigned to test and evaluation units as well as a few utility and composite squadrons.

The F-4B was the first major production version of the Phantom, and it was built in larger numbers than any other Navy variant with a total of 649 being delivered. The F-4B was equipped with the AJB-3 bombing system and could carry a wide variety of weapons on five hardpoints beneath the fuselage and wings. It was the first jet fighter in the Navy to enter service without an internal cannon, and this would later prove to be a mistake. Instead, four AIM-7 Sparrow radar guided missiles were carried in recessed bays beneath the fuselage. These were to be the Phantom’s primary weapon in its intended role of fleet defense interceptor. The capability to carry AIM-9 Sidewinder infrared guided missiles was added, and these were mounted on launch rails attached to the sides of the two inboard wing pylons.

Two of the reasons the Phantom won the fly-off with the Crusader III were that it had two seats and two engines. The Navy wanted the radar intercept officer (RIO) in the back seat to control the radar and guide the pilot to the enemy aircraft during an engagement. The Navy’s position was that a two man team was more efficient because it spread out the work load. The Navy also preferred two engines since they provided an extra margin of survivability and reliability which was very important over vast expanses of ocean. But another point in the Phantom’s favor was that it could carry a large load of bombs, rockets, guided missiles, and other ordnance that could be used against ground targets. It was a relatively short time before this fighter-bomber capability was first put to use in Vietnam. While Phantoms would score many of the Navy’s air-to-air victories against enemy aircraft in Vietnam, they also joined the Navy’s attack aircraft in delivering a wide variety of ordnance against targets on the ground.

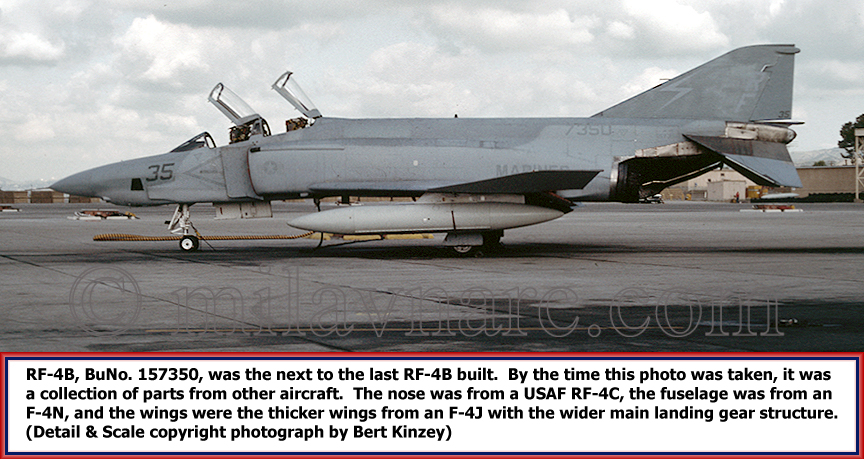

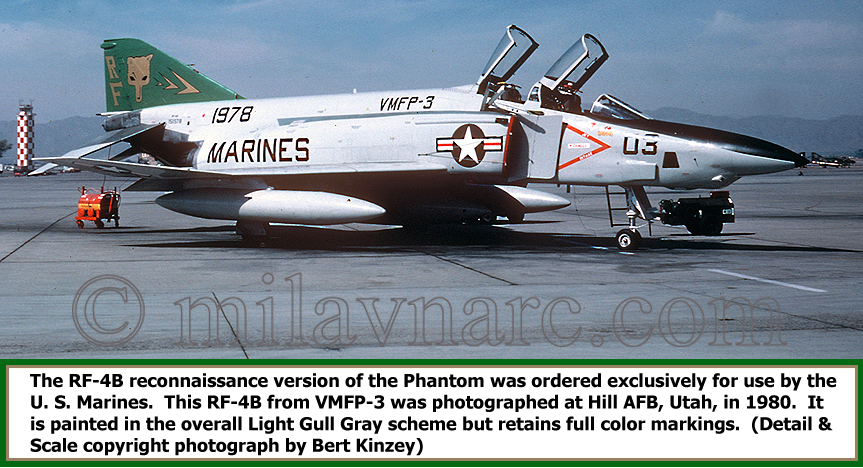

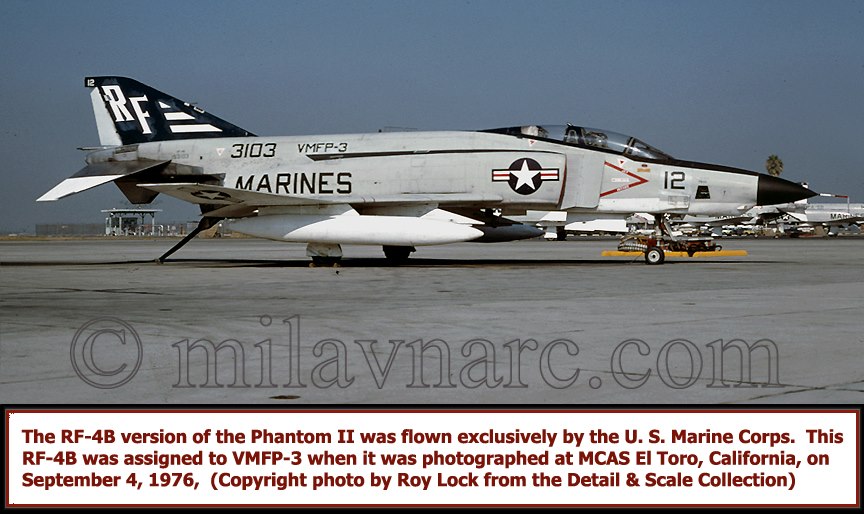

Once the Air Force acquired its first Phantoms, it developed a dedicated reconnaissance version designated the RF-4C. The Navy had not originally planned to have a reconnaissance version of the Phantom, preferring to use the RF-8 Crusader and RA-5C Vigilante instead. However, the Marine Corps did need a new reconnaissance aircraft, so the Navy decided to have forty-six F-4Bs completed with an elongated nose section similar to that on the RF-4C. This modified nose had positions for vertical, oblique, and forward-looking cameras, and all forty-six of the aircraft were assigned to the Marines. The last ten RF-4Bs were built with the thicker wings and wider wheels and tires used on the F-4J and on Air Force Phantoms. The last three were built with a more rounded nose section which unfortunately precluded repositioning of the cameras while in flight. Unlike Air Force RF-4Cs, which could deliver a tactical nuclear weapon, RF-4Bs were completely unarmed.

Twelve F-4Bs were converted to F-4Gs with an ASW-21 two-way digital data link and an approach power compensation system for automatic carrier landings. Painted in an unusual green camouflage scheme, these F-4Gs were assigned to VF-213 which made a deployment to Vietnam aboard USS KITTY HAWK, CVA-63, to evaluate the system. This test proved successful and the feature became standard on the subsequent F-4J. The F-4Gs were converted back to F-4B standards, thus freeing up the F-4G designation to be used again on the Air Force’s Wild Weasel version.

The second production version of the Phantom developed for the Navy was the F-4J. This was a considerable improvement over the F-4B, and the F-4J could be visually distinguished from the earlier variant by its lack of an infrared sensor under the radome and by the larger exhaust nozzles on its engines. The F-4J also had wider main landing gear wheels and tires, and a thicker inner wing section was required to accommodate them when the gear was retracted. This wider landing gear had been used on the Air Force versions, and it proved to be better for operating from land bases.

To improve the Phantom’s capabilities in the interceptor role, the AWG-10 missile control system and its pulse doppler APG-59 radar were installed in the F-4J. The AJB-7 bombing system enhanced the F-4Js ability to attack targets on the ground. Communications, navigation, and IFF systems were upgraded with solid state electronics. More powerful J79-GE-10 engines were installed, each of which produced 17,900 pounds of thrust in afterburner.

Experience in Vietnam had demonstrated the need for electronic countermeasures and threat warning devices. Throughout the war, improved radar homing and warning (RHAW) gear was added to the Phantom and other aircraft, and these often showed up as antenna fairings on the tail and elsewhere. During its service, antenna fairings were added near the upper edge of each air inlet of the F-4J.

F-4Js gradually took the place of F-4Bs in fleet squadrons, but they never entirely replaced the older variant. When production ended, a total of 522 F-4Js had been built.

In 1971, the Navy began an extensive program to update and improve F-4Bs. The 227 Phantoms that went through this upgrade were then redesignated F-4Ns. A visual identifying feature of the F-4N was the addition of antenna fairings along the upper side of each intake. These were similar to the ones used on the F-4J, but they were considerably longer. But most improvements were internal and could not be detected by the eye. A Visual Target Acquisition System (VTAS) was added, as was a Sidewinder Expanded Acquisition Mode (SEAM). The airframe was strengthened to increase service life, and a new electrical generating system was added. All wiring and connectors were replaced. A new dogfight computer was added, as was an improved air-to-air identification friend-of-foe (IFF) system. These changes permitted the F-4N to remain in service into the 1980s, more than twenty years after the original airframes had been delivered as F-4Bs.

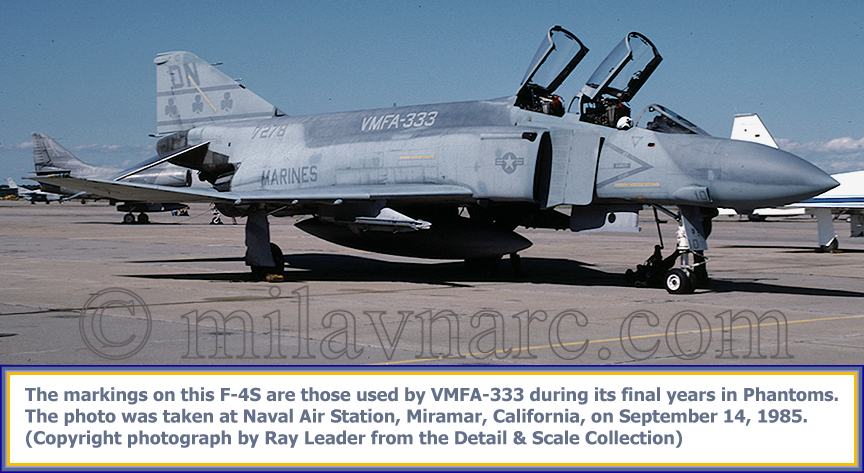

In 1975, a similar and more extensive upgrade was begun on the F-4J. The 302 aircraft that went through this program were given the F-4S designation. This again included structural strengthening to increase the service life of the airframes, but the most important change was the addition of maneuvering slats along the leading edge of the wings. These were like those fitted to late production Air Force F-4Es and converted F-4G Wild Weasels. Another important improvement made on the F-4S, as well as on some late F-4Js, was the change to a low-smoke engine. In Vietnam the huge smoke trail left by the J79 was often criticized, because it exposed the presence and location of the Phantom to an enemy pilot long before the aircraft itself could be seen. Unfortunately the problem was not solved until long after the war in Vietnam had ended.

By the end of 1986, Phantoms had been retired from the Navy’s active and reserve squadrons. This was more than five years before the last Phantoms were retired from the U. S. Air Force. A few served on as remotely controlled drones and were designated QF-4B, QF-4N, and QF-4S.

The importance of the Phantom to carrier based aviation in the U. S. Navy cannot be overstated. It proved to all the critics that the most capable and powerful jet fighters could operate from carriers, thus helping insure the future of the large deck supercarriers for many years to come.

___________________________________________________________

F-4B SPECIFICATIONS & DATA

Wingspan 38 feet, 5 inches

Wing Area 530 square feet

Length 58 feet, 3.75 inches

Height 16 feet, 3 inches

Weight

Empty 28,000 pounds

Gross 44,600 pounds

Combat 38,500 pounds

Max T. O. 54,600 pounds

Landing 34,000 pounds (arrested)

Speed

Max 1,485 mph at 48,000 feet

Cruising 575 mph

Stall 95 mph

Rate of Climb

1 minute 28,000 feet

Ceiling

Service 62,000 feet

Combat 56,850 feet

Maximum Range 2,300 feet

F-4J SPECIFICATIONS & DATA

Wingspan 38 feet, 5 inches

Wing Area 530 square feet

Length 58 feet, 3.75 inches

Height 16 feet, 3 inches

Weight

Empty 30,770 pounds

Gross 46,833 pounds

Combat 41,400 pounds

Max T. O. 59,000 pounds

Max Speed 1,584 mph at 48,000 feet

Rate of Climb

1 minute 41,250 feet

Ceiling

Service 70,000 feet

Combat 54,700 feet

Maximum Range 1,956 miles

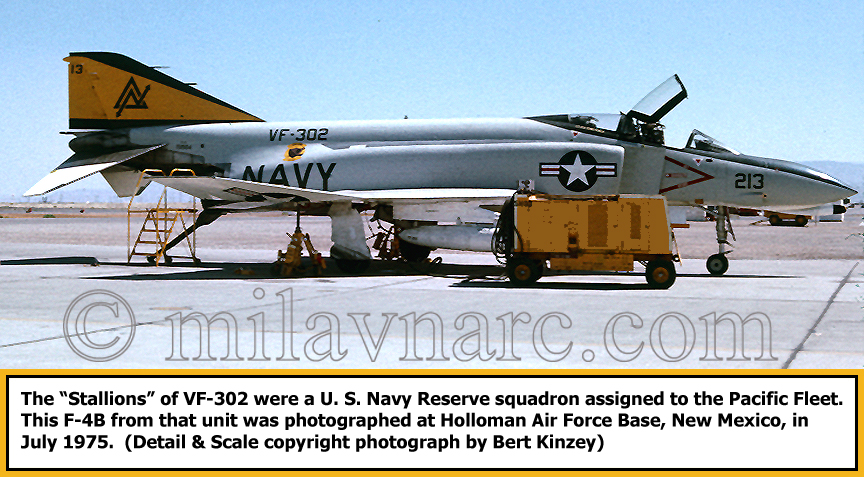

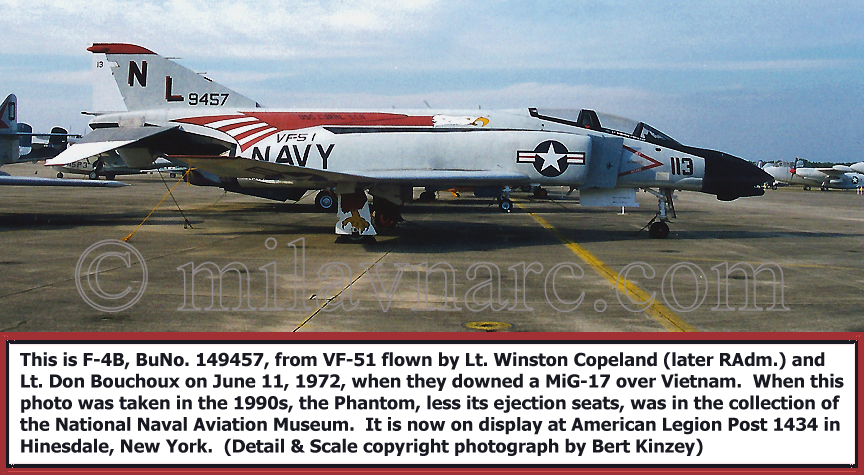

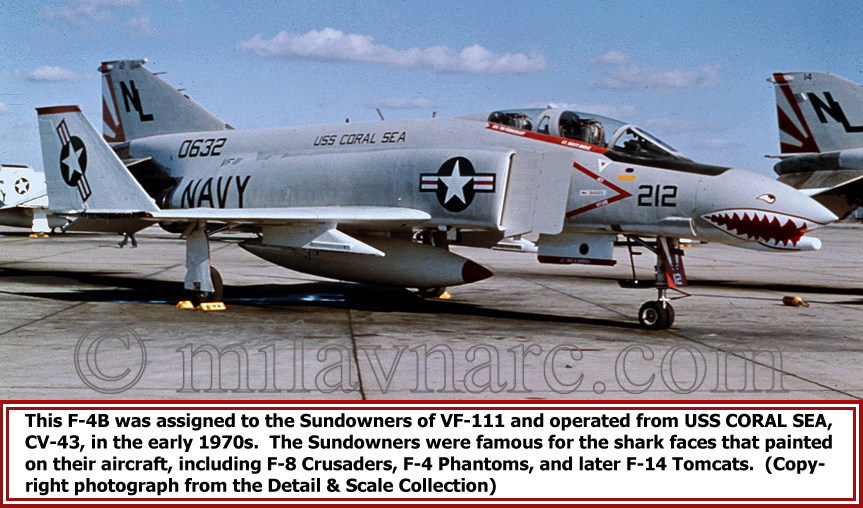

F-4B, U. S. Navy

General Photo Set:

This photo set contains general photographs of U. S. Navy F-4B Phantom IIs not included in other more specific photo sets of Navy F-4Bs.

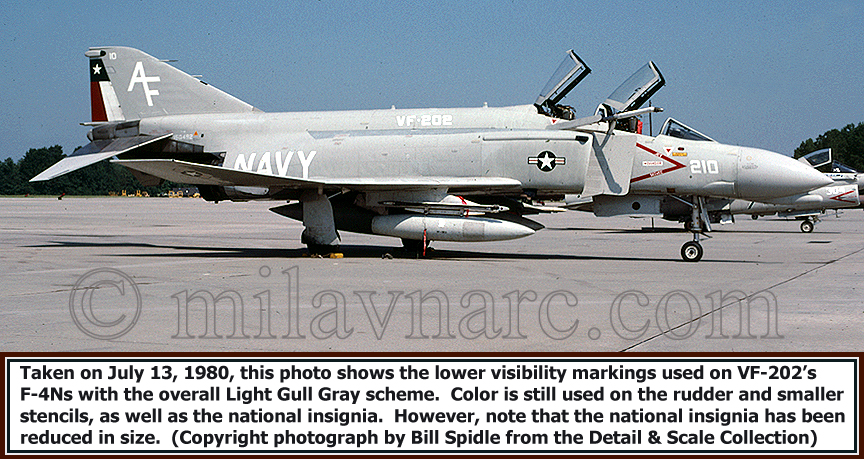

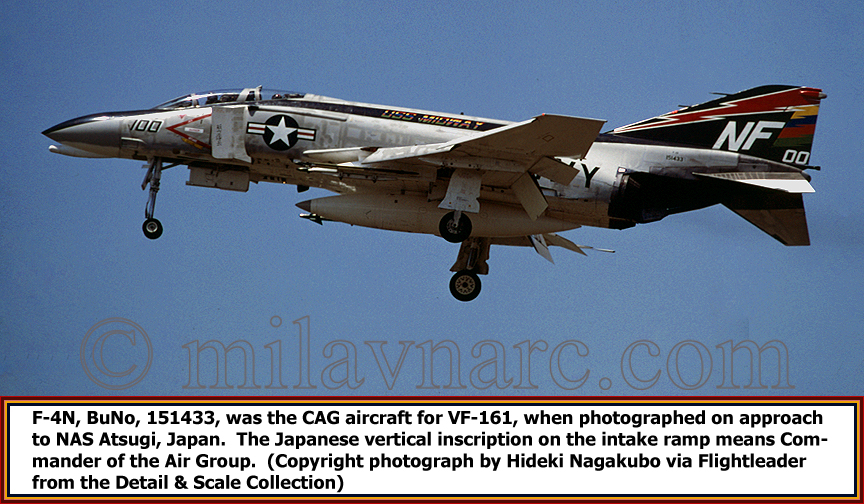

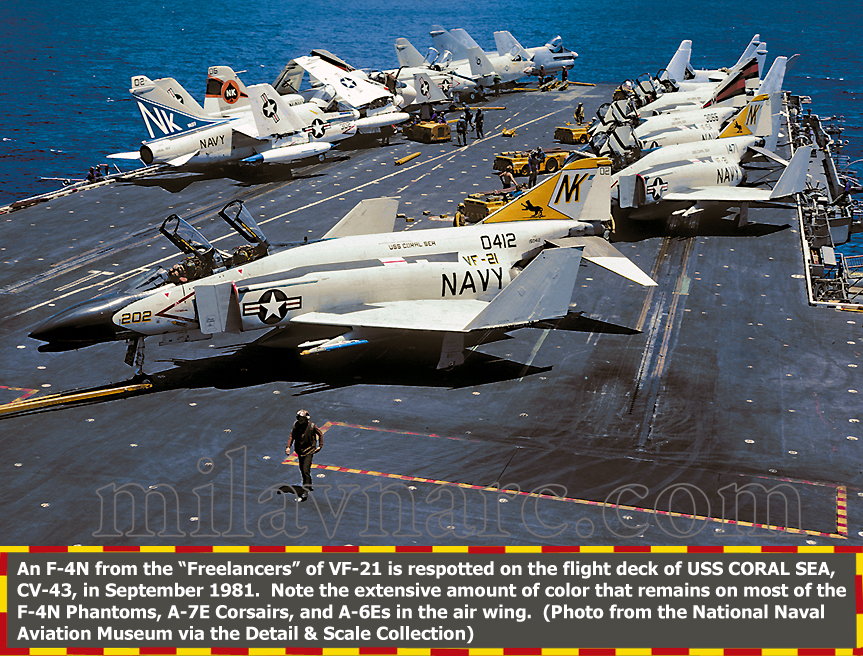

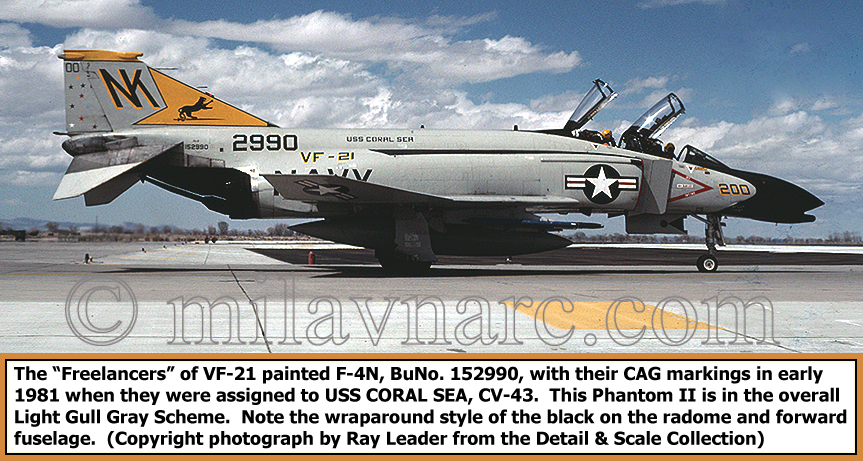

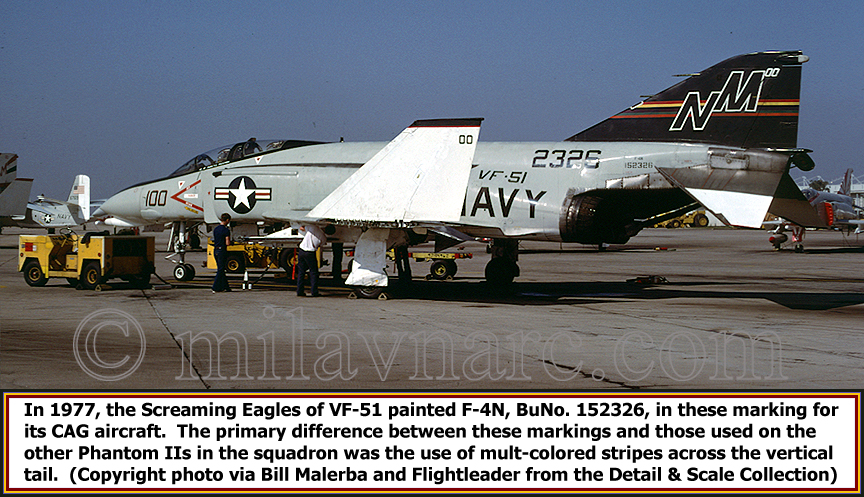

F-4N, U. S. Navy

General Photo Set:

This photo set contains general photographs of U. S. Navy F-4N Phantom IIs not included in other more specific photo sets of Navy F-4Ns.

F-4J, U. S. Navy

General Photo Set:

This photo set contains general photographs of U. S. Navy F-4J Phantom IIs not included in other more specific photo sets of Navy F-4Js.

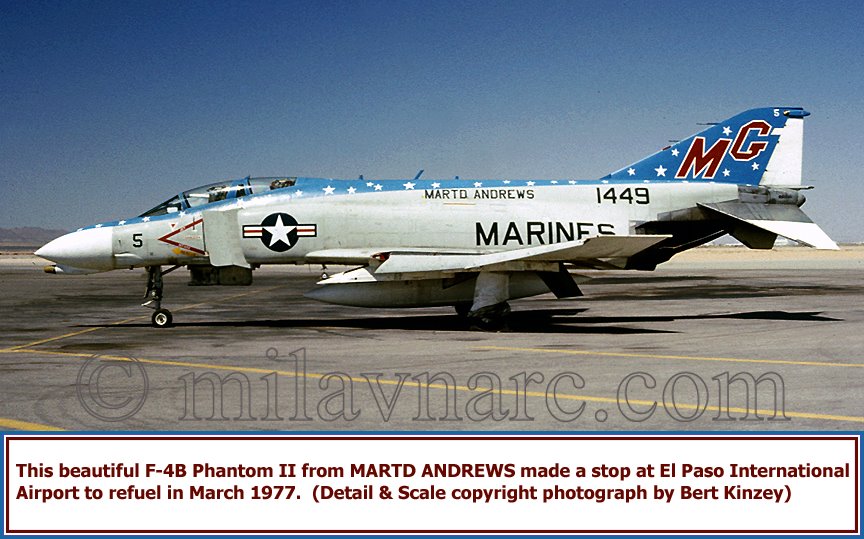

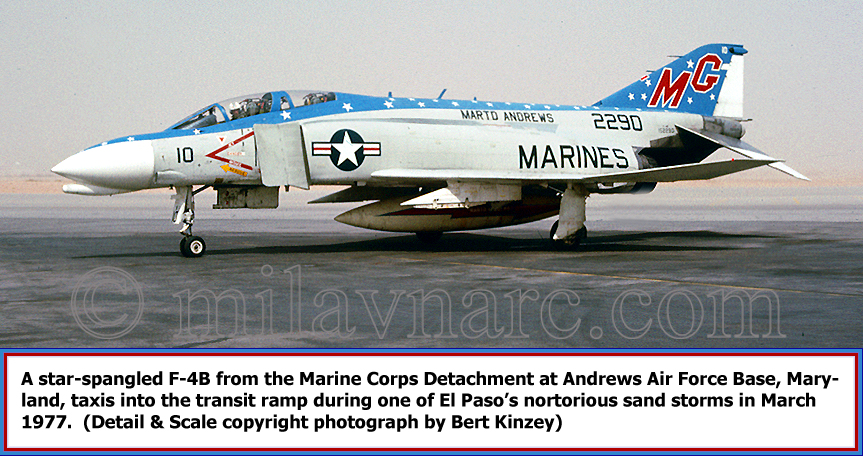

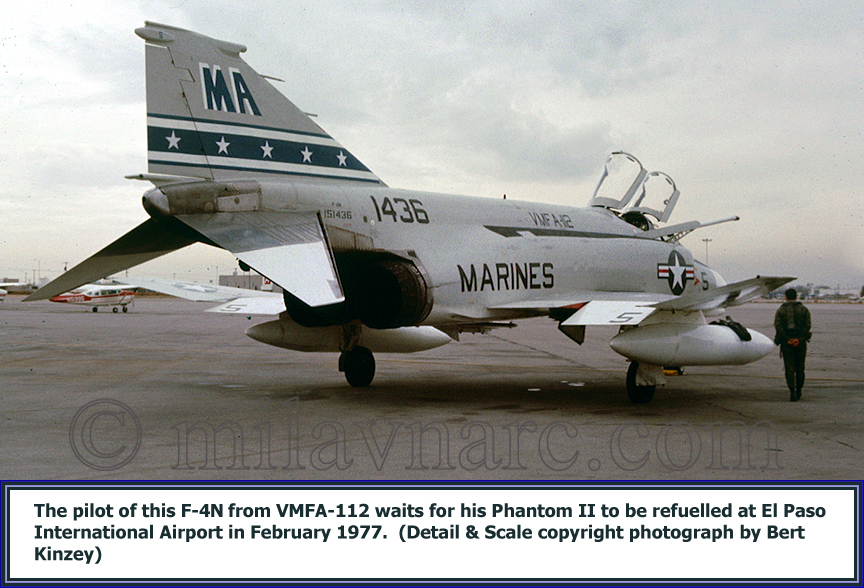

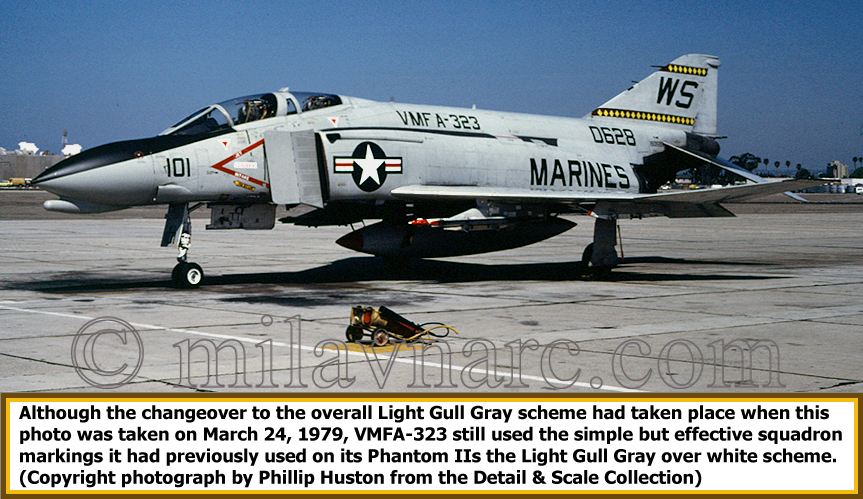

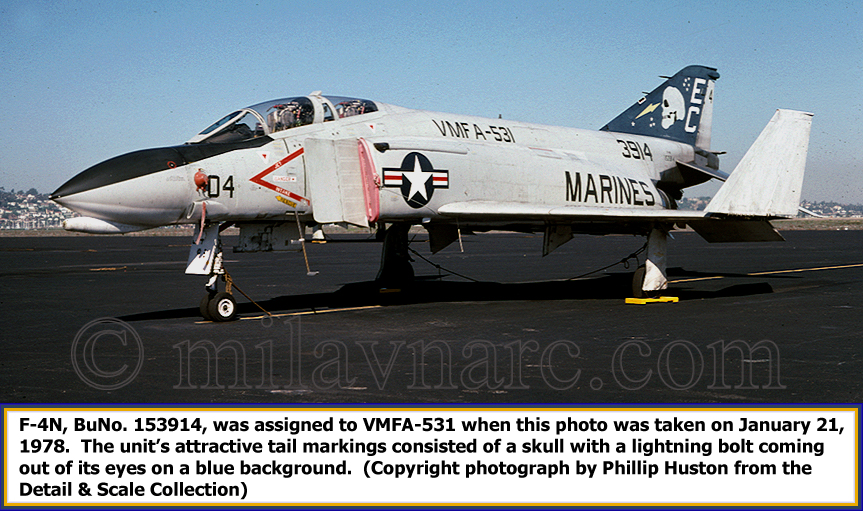

F-4B/N, U. S. Marine Corps

General Photo Set:

This photo set contains general photographs of U. S. Marine Corps F-4B and F-4N Phantom IIs not included in other more specific photo sets of Marine Phantoms..

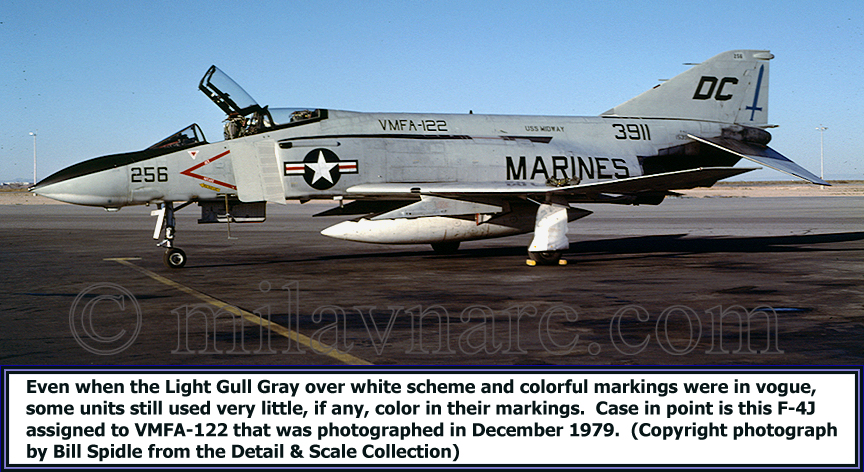

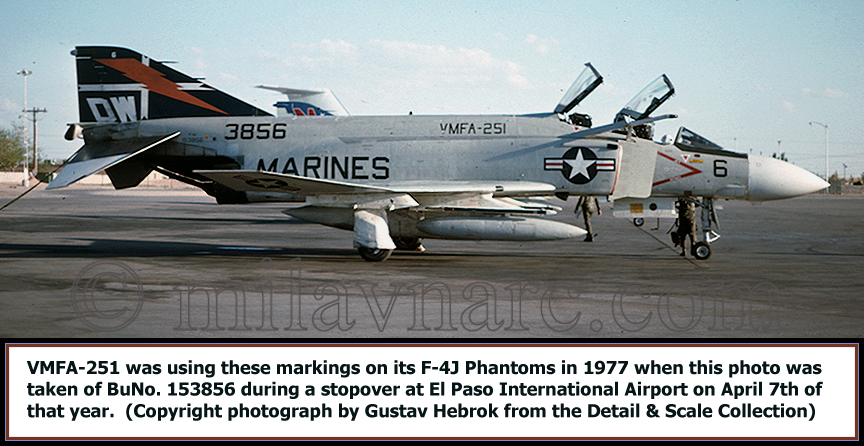

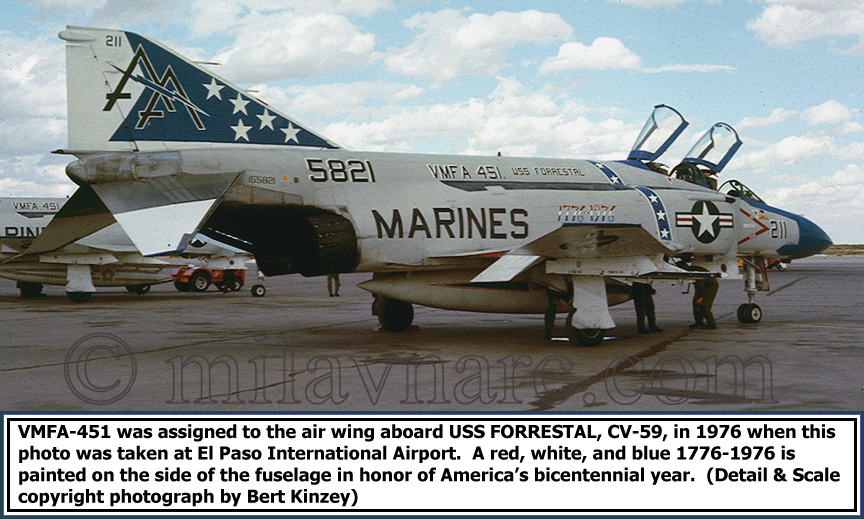

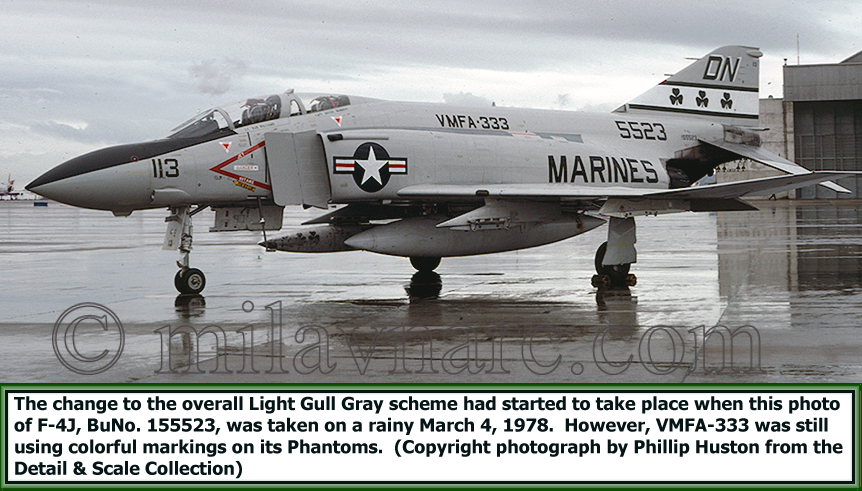

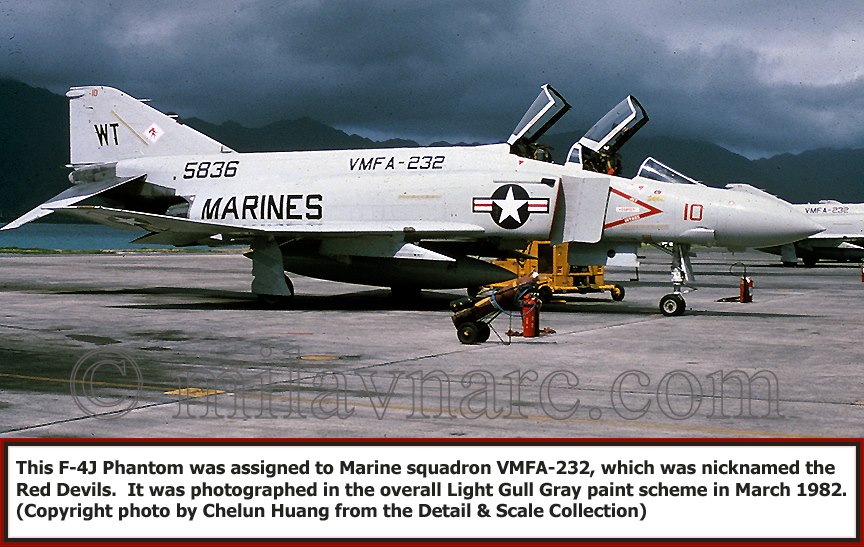

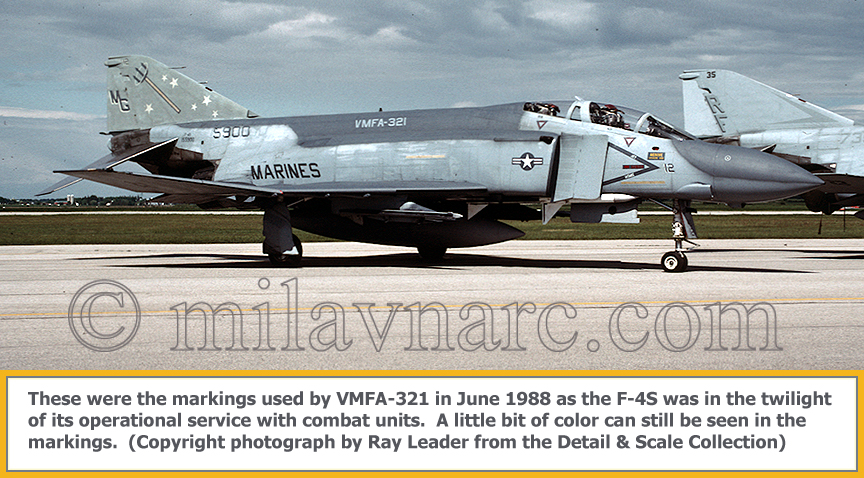

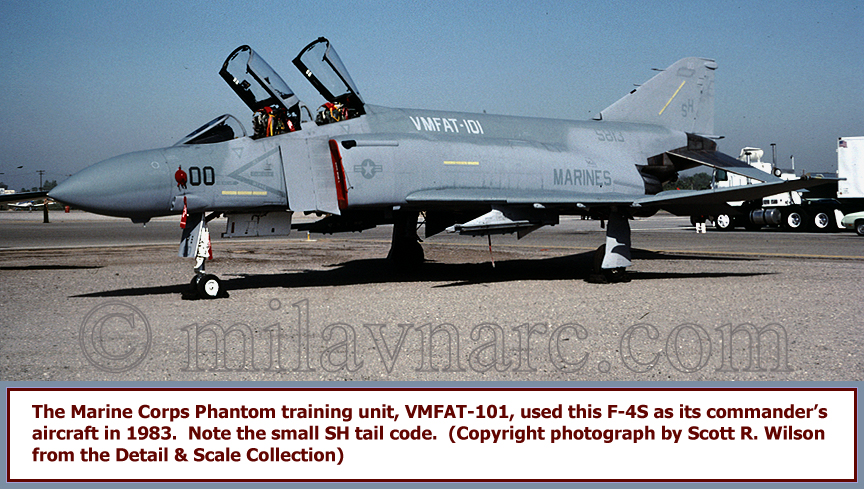

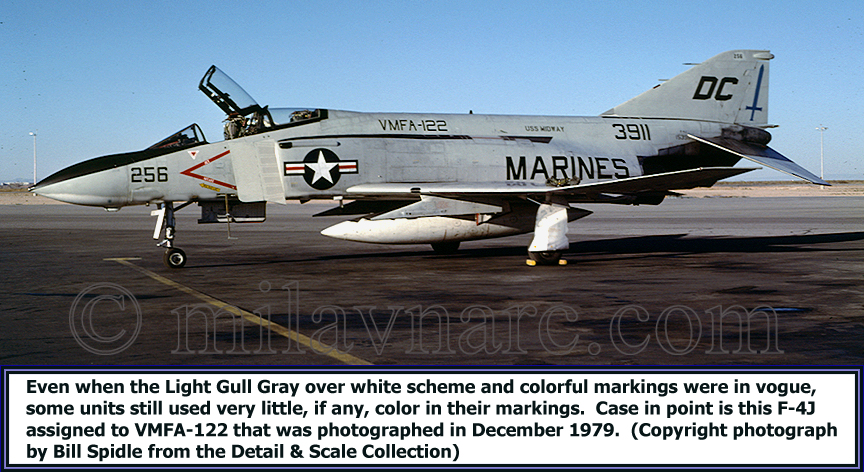

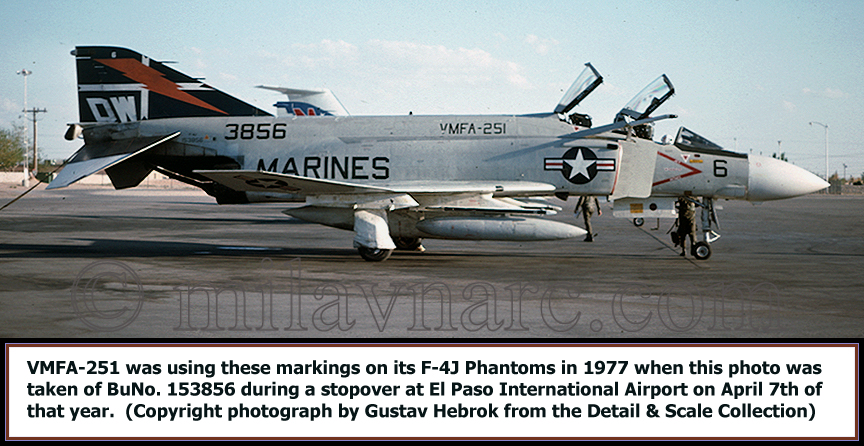

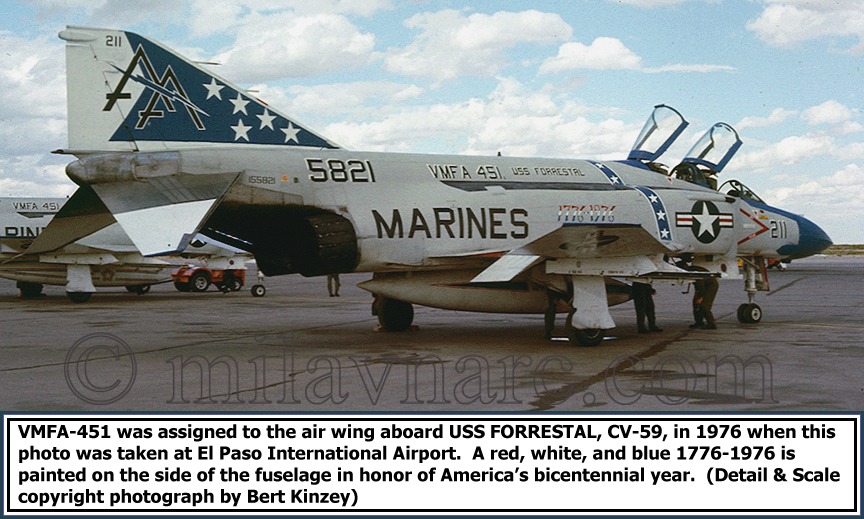

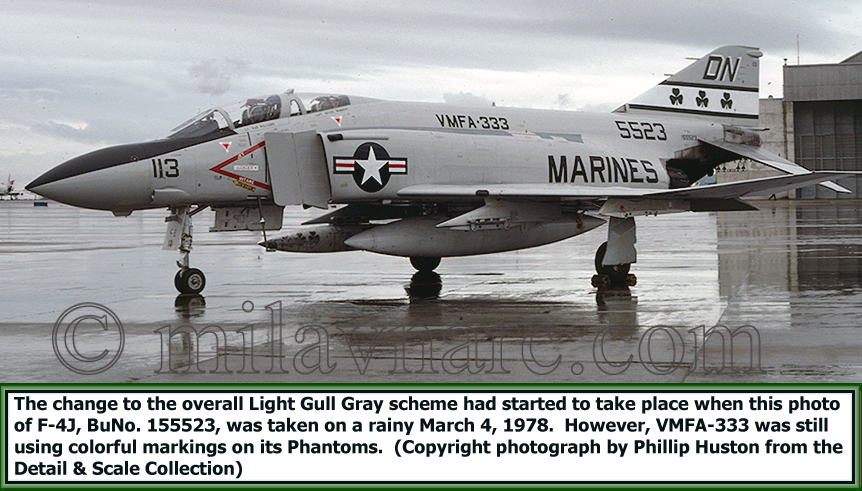

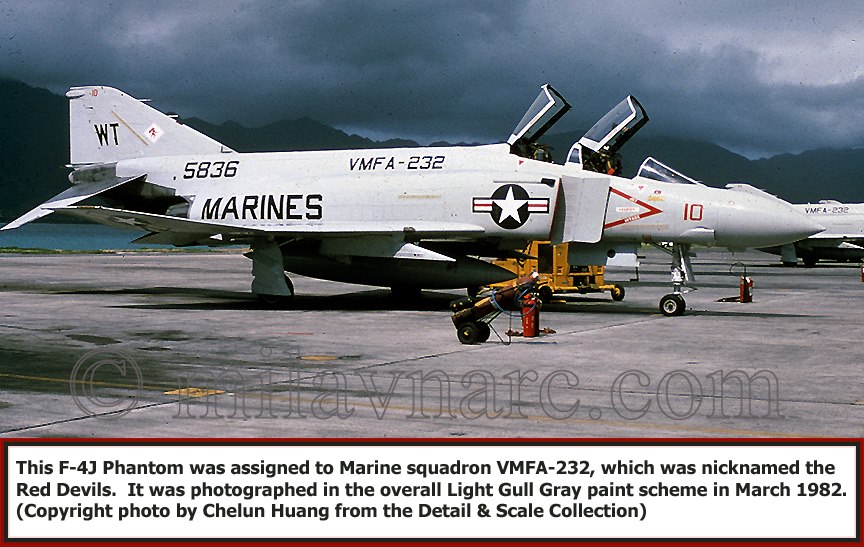

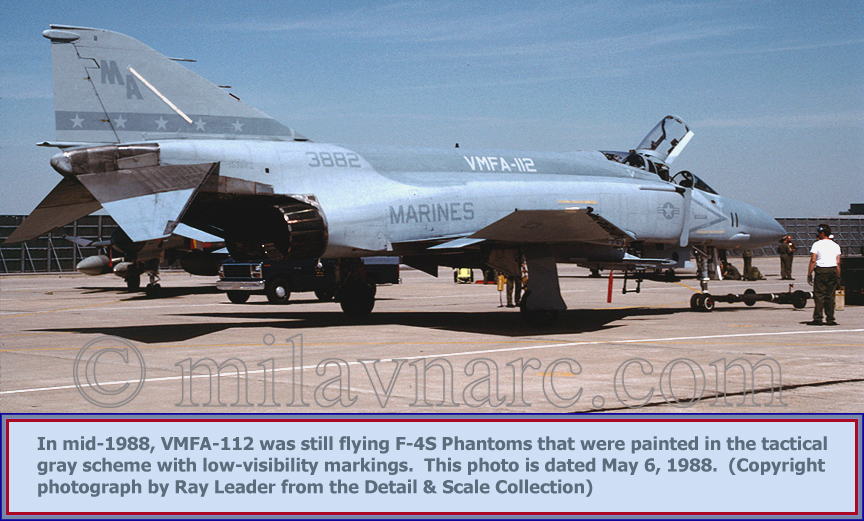

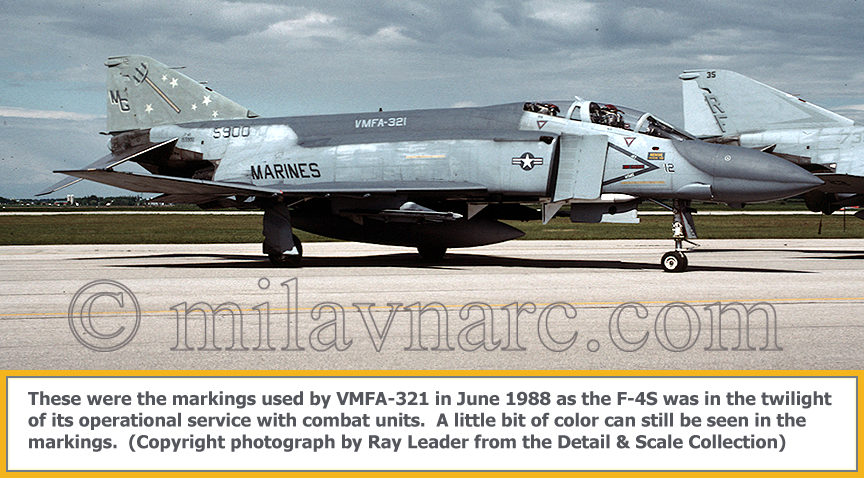

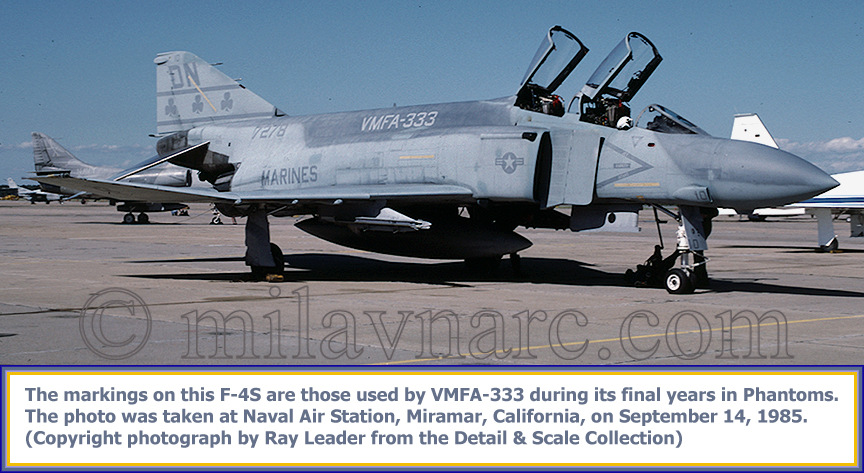

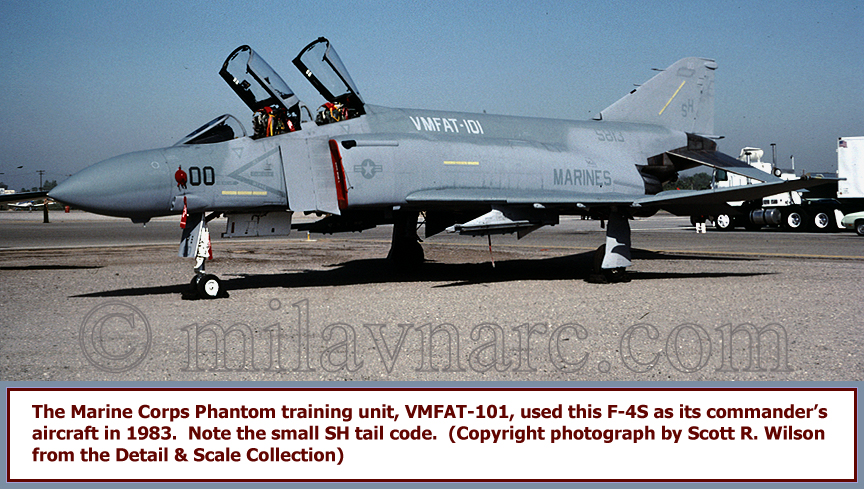

F-4J/S, U. S. Marine Corps

General Photo Set:

This photo set contains general photographs of U. S. Marine Corps F-4J and F-4S Phantom IIs not included in other more specific photo sets of Marine Phantoms.

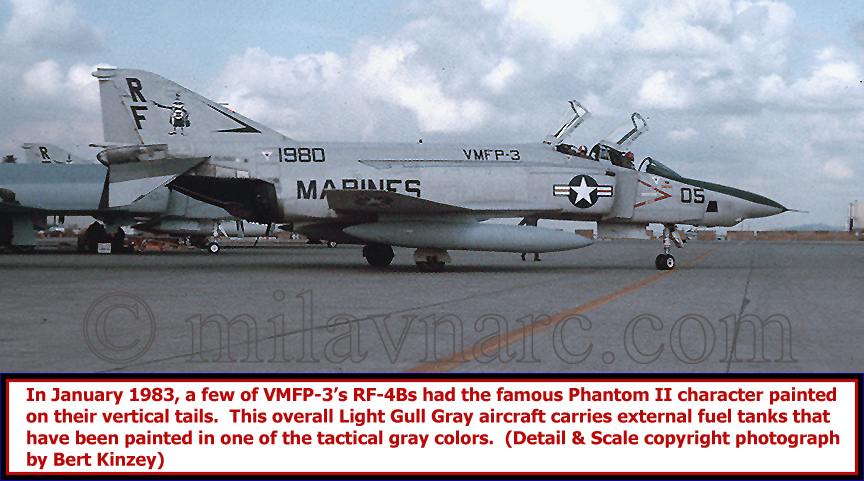

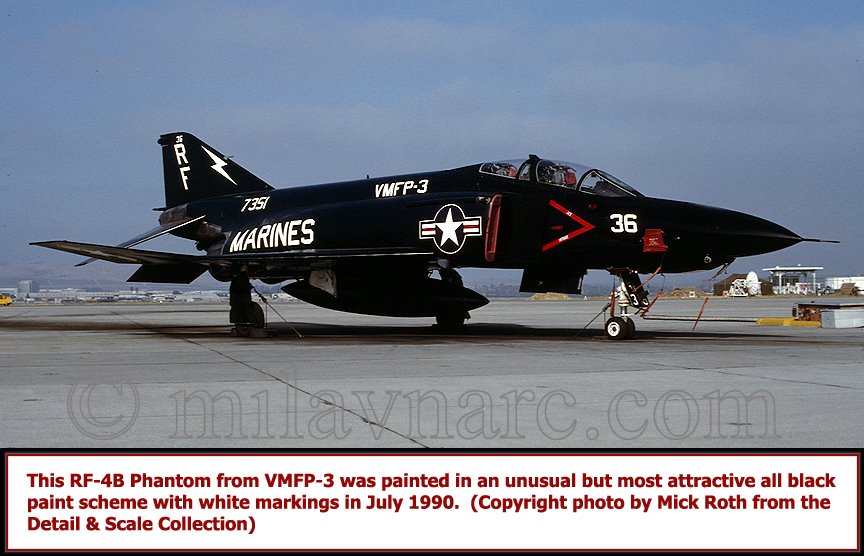

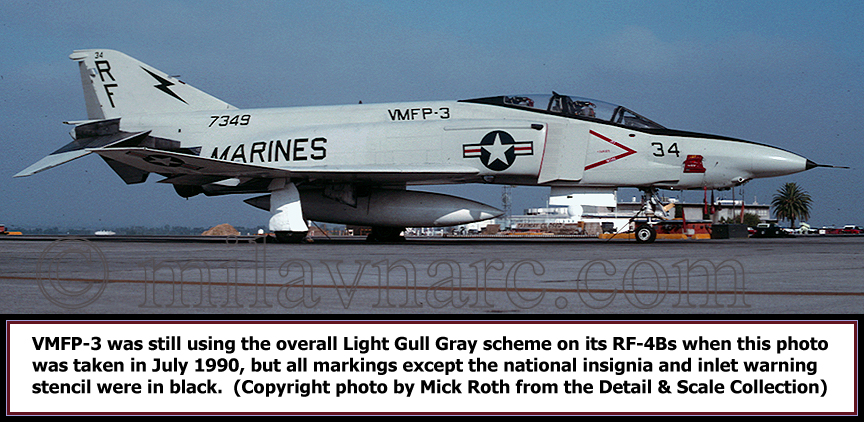

PRF-4B, U. S. Marine Corps

General Photo Set:

This photo set contains general photographs of U. S. Marine Corps RF-4B Phantom IIs not included in other more specific photo sets of F-4 Phantoms.